Parsons, Sadie

GEOG 490

Dr. Amador

May 5, 2016

Abstract

Agricultural runoff from corn farms in Iowa is believed to contribute to the growing dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico (Beman et al., 2005; Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, 2016). This natural, but mostly human induced phenomenon (Simmon, 2012), also termed a hypoxic (low oxygen) zone, is partially driven by an increase in the demand for food and biofuel production, prompting farmers to have a heavier reliance on phosphorus- and nitrogen-rich fertilizers. Loose topsoil containing these phosphorus and nitrogen-rich fertilizers are transported into streams during heavy rainfall events (mainly in springtime), travelling through the Mississippi River system and emptying into the Gulf of Mexico. The excess nutrient loading creates massive algae blooms and subsequent hypoxic conditions. The growing number of hypoxic zone events contributes to the range of this dead zone, spanning 6,474 square miles as of August 3, 2015. (Simmon, 2012). These events contribute to massive fish kills which threatens fisheries and a large human food source (Altieri & Gedan, 2014; Bruckner, 2012). Analysis of this urgent manmade problem relates trends in Iowa corn production to the increasing dead zone conditions in the Gulf of Mexico during 2010-2015. To mitigate these effects, this work seeks to better understand our current farming practices and to assess alternative techniques that are believed to be less impactful on the hydrologic environment.

Introduction

Our oceans are dying, and humans play a large role in their current and future health. Agricultural practices are believed to be part of the reason why there is a growing hypoxic or “dead zone” in the marine ecosystem in the Gulf of Mexico. A dead zone is an area in the ocean that cannot support life because of its hypoxic conditions (lacking oxygen) (Simmon, 2012). This particular dead zone in the Gulf spans from the mouth of the Mississippi River covering 6,474 square miles as of August 3, 2015. Nancy Rabalais, the executive director of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCOM) states, “the Dead Zone off the Louisiana coast is the second largest human-caused coastal hypoxic area in the global ocean.” With our current food and biofuel demands, the dead zone can only spread over more territory. The Gulf of Mexico provides 72% of U.S. harvested shrimp, 68% of harvested oysters, and 16% of commercial fish (Bruckner, 2012). Fisherman, economies, and our food source will be severely threatened even more if this 5,052 square mile dead zone spreads.

This research seeks to analyze corn production in Iowa, which is one of the many states that contributes to agricultural runoff to the Mississippi River. Correlating this data with different rainfall events to different hypoxic events, their intensities, and massive fish/organism kills in the Gulf of Mexico will allow us to understand the amount of human impact on the environment in regards to agricultural practices and its consequences downstream. As a result, we will be able to identify different mitigation strategies to reduce human impact on the environment through different agricultural practices.

Background

In Iowa, corn has been the largest produced crop for almost the last two decades (Iowa Corn Growers Association, 2016). Due to current human demands for food and biofuel, farmers have incorporated Phosphorous and Nitrogen rich fertilizers to their crops. These are the two main nutrients in agricultural runoff that contribute to nutrient loading.

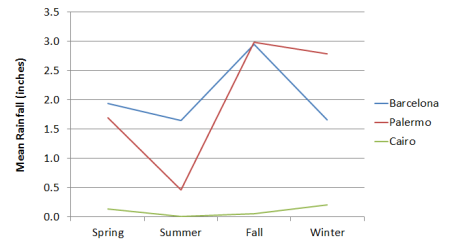

After heavy rainfall events (primarily during the springtime), the increased nutrients, phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N), in the topsoil are transported into the fluvial system eventually making its way into the Mississippi River. Microscopic plants called phytoplankton thrive as these nutrients become more concentrated in a process known as eutrophication. These are generally seen as algae blooms. After the phytoplankton expend the nutrients, they die and sink to the bottom where bacteria eat them while consuming and depleting the oxygen in the process (Beman et al., 2005; Bruckner, 2012; Rabotyagov et al., 2014; Simmon, 2012)

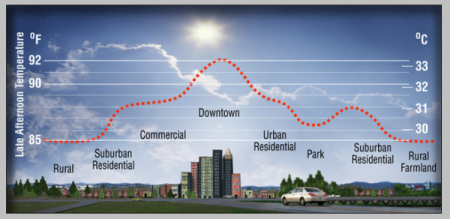

Different densities of ocean water creates a thermocline, which is the transition layer between warmer and cooler water (NOAA, 2016). here some areas contain no oxygen zone where organisms cannot survive (Beman et al., 2005; Bruckner, 2012; Rabotyagov et al., 2014; Simmon, 2012).Naturally, the tides and waves restock this consumed oxygen from the air and it mixes down to the bottom; however, during the summer months fresh, less dense, warmer surface water sits on top of colder, more saline, denser water and creates a barrier between the two water bodies, therefore limiting the amount of oxygen that can be replenished. This stratification leaves the bottom layer with little to no oxygen that cannot sustain life, called a hypoxic or dead zone (Murray, 2010; Rabotyagov et al., 2014). The Gulf of Mexico, The Chesapeake Bay, Scandinavia’s Kattegat Strait, the mouth of the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea and the northern Adriatic are only a few of the 550 dead zones worldwide, largely influenced by mankind’s impact on their environment in various polluting ways (Simmon, 2012).

Methodology

Data collected included: county-level fertilizers, precipitation events, and the hypoxic area in the Gulf of Mexico. I compared fertilizer usage and precipitation to the extent of the hypoxic area.

Acquisition of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) county-level estimates of Phosphorous and Nitrogen (kg) use (2001-2006) (Figure 2- Figure 7). The values for Nitrogen use on farms range from 0 – 25,000,000 kg, while values for Phosphorus use on farms range from 0 – 5,000,000 kg. Data was aggregated into five categories between these ranges and color coded them by value. The yellow represents lower amounts of Phosphorus and the red represents higher amounts of Phosphorus. Since they had the same values associated with their colors, they were easy to compare throughout the years listed.

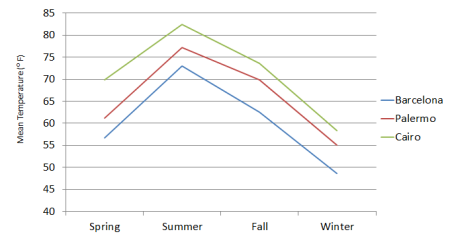

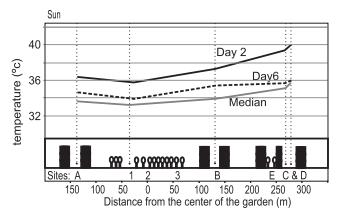

Precipitation amount data for statewide ranks were acquired from February to July in 2010 to 2015 from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) (Figure 1).

| Year | Precipitation | Wetness Rank | Hypoxic Area (mi2) |

| 2010 | 114/116 | 2 | 7,722 |

| 2011 | 87/117 | 5 | 6,757 |

| 2012 | 14/118 | 6 | 2,896 |

| 2013 | 114/119 | 1 | 5,792 |

| 2014 | 103/120 | 3 | 5,405 |

| 2015 | 96/121 | 4 | 5,405 |

The data of Hypoxic extent in the Northern Gulf of Mexico were acquired from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which represents the area in square miles of hypoxic conditions (Figure 1).

County-level maps of Iowa displaying Nitrogen and Phosphorus on farms, as well as perennial streams of Iowa were generated using ArcMap (figure 11).

Results & Conclusions

High Phosphorus and Nitrogen levels combined with high precipitation years correlates with different areas (mi2) of hypoxic conditions in the Gulf of Mexico. Due to the time difference of county-level estimates of Nitrogen and Phosphorus use on farms from 2001 to 2006 (Figure 2- Figure 7), and precipitation events from 2010 to 2015 (Figure 8- Figure 10), a direct relationship between the data cannot show a direct linkage to the extent of the hypoxic area in the Gulf. However, according to the literature (e.g., Beman et al., 2005; Bruckner, 2012; Rabotyagov et al., 2014; Simon, 2012), Nitrogen and Phosphorus are the two main nutrients that drive algal blooms and their subsequent hypoxic conditions. Therefore, despite the time gap in data sets, higher amounts of Nitrogen and Phosphorus in addition to more rainfall events are expected to correlate with the extent of hypoxic area (mi2) in the Gulf of Mexico.

Years with more precipitation in Iowa are correlated with higher hypoxic conditions. Years 2010 (Figure 8), 2011 (Figure 9), and 2014 were the three wettest years for Iowa between the 2010 to 2015 study period and all correlate with high hypoxic areas (7,722 mi2, 6,757 mi2, and 5,405 mi2) (Figure 1 & Figure 12). Years with less precipitation in Iowa are correlated with lower hypoxic conditions, such as 2012 with a correlating hypoxic area of 2,896 mi2. This remains true except in 2011 where the Gulf had a hypoxic area of 6,757 mi2. To explain the apparent 2011 anomaly, other surrounding states within the Mississippi River watershed (e.g., Ohio, Louisiana) experienced much above normal precipitation events and record wettest levels of precipitation. Therefore, the presence of additional states in the Mississippi River watershed influence the amount of nutrient transport into the Gulf of Mexico; Iowa is not the only state that contributes nutrients to the dead zone.

Further Work

More precise and current Nitrogen and Phosphorus inputs data for Iowa will help to further understand the influence of agricultural runoff on hypoxic conditions in the Gulf of Mexico. Additionally, a larger set of data from other bordering states around the Mississippi will help fill the gaps between which state(s) are most influential on nutrient inputs in the Mississippi River watershed and the downstream Gulf of Mexico. This may allow us to identify different agricultural production methods to reduce our impact on the environment.

Works Cited

Altieri, A. H. and Gedan, K. B., 2015. Climate change and dead zones. Global Change Biology. Vol

- P 1395- 1406. http onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12754/epdf://.

Beman, J. M. Arrigo, K.R., Matson, P.A. 2005. Agricultural runoff fuels large phytoplankton

blooms in vulnerable areas of the ocean. Nature. 434, 211-214

Bruckner, M. 2012. The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone. Science Education Resource Center.

http://serc.carleton.edu/microbelife/topics/deadzone/index.html

NOAA. 2016. National Temperature and Precipitation Maps. Statewide Precipitation Ranks

February- July. Department of Commerce. http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/temp-and-precip/us-maps/6/201507?products[]=statewidepcpnrank.

NOAA. 2015. Ocean Facts. What is a thermocline? National Ocean Service.

http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/thermocline.html

Rabotyagov, S. S., Kling, C. L., Gassman, P. W., Rabalais, N. N., Turner, R. E. 2014. The Economics

of Dead Zones: Causes, Impacts, Policy Challeneges, and a Model of the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxic Zone. Iowa State University. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. Vol 8, issue 1. P 58-79.

Simmon R. 2012. What Causes Ocean “Dead Zones”?. Scientific American.

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ocean-dead-zones/

Posted by smparson

Posted by smparson